You Changed the Data. Can You Prove When and Why?

A hands-on Quarkus and Hibernate Envers tutorial for building real audit trails in enterprise Java systems.

The email arrived at 07:42 on a Tuesday, which is exactly when bad news likes to surface. A large enterprise customer had discovered that a credit limit was changed twice within minutes, then quietly reverted before the nightly batch ran. The database showed the final value. The logs showed nothing unusual. Compliance wanted names, timestamps, and intent. We had none of it.

The system worked. The business logic was correct. The failure was architectural. We had no reliable audit trail at the domain level, only application logs that were never designed to answer legal questions. In distributed Java systems, state changes happen inside transactions, not log files, and once those transactions commit, history is gone unless you explicitly persist it.

This is the gap Hibernate Envers exists to close, and Quarkus makes it practical to do so without turning your persistence layer into a mess.

The Domain: Credit Limits That Must Be Explained

We are building a small credit account service. It exposes a REST API to create accounts, update credit limits, and suspend access. Every change must be traceable. We need to know what changed, when it changed, and who changed it. Not in theory. In production.

This tutorial walks through that system end to end, not as a demo, but as something you could defend in an audit meeting.

Bootstrapping the Service

You need Java 21, Maven, a running PostgreSQL instance or Podman and a running Podman Machine for Quarkus Dev Services, and the Quarkus CLI.

We start clean, because Envers is something you add deliberately, not something you retrofit casually. If you want, you can also directly clone the project from my repository.

quarkus create app com.mainthread.audit:credit-audit \

--extension=quarkus-rest-jackson,hibernate-orm-panache,hibernate-envers,jdbc-postgresql

cd credit-auditWe include Panache because we want explicit, readable domain code. We include Envers because auditing belongs in the persistence layer, where transactions live. We use quarkus-rest to keep the example aligned with current Quarkus guidance.

The CreditAccount Aggregate

Auditing only works if your domain model is honest. If state is scattered across tables or hidden in JSON blobs, Envers will faithfully record confusion.

Here is the core entity.

package com.mainthread.audit.domain;

import org.hibernate.envers.Audited;

import io.quarkus.hibernate.orm.panache.PanacheEntity;

import jakarta.persistence.Entity;

import jakarta.persistence.EnumType;

import jakarta.persistence.Enumerated;

@Entity

@Audited

public class CreditAccount extends PanacheEntity {

public String owner;

public long creditLimit;

@Enumerated(EnumType.STRING)

public Status status;

public enum Status {

ACTIVE,

SUSPENDED

}

}The @Audited annotation is deceptively simple. It tells Hibernate to generate parallel audit tables and record every state transition inside the same transaction that mutates the entity. If the transaction rolls back, the audit entry rolls back with it. That property alone eliminates an entire class of consistency bugs.

Schema Generation and What Envers Actually Creates

This is the moment where Envers stops being “magic” and starts being something you can reason about under pressure.

When Quarkus boots with Hibernate ORM and Envers enabled, schema generation does not just create your domain table. It creates a parallel history model that mirrors your transactional reality. Understanding that model is essential, because every audit query you run later is constrained by these tables and their semantics.

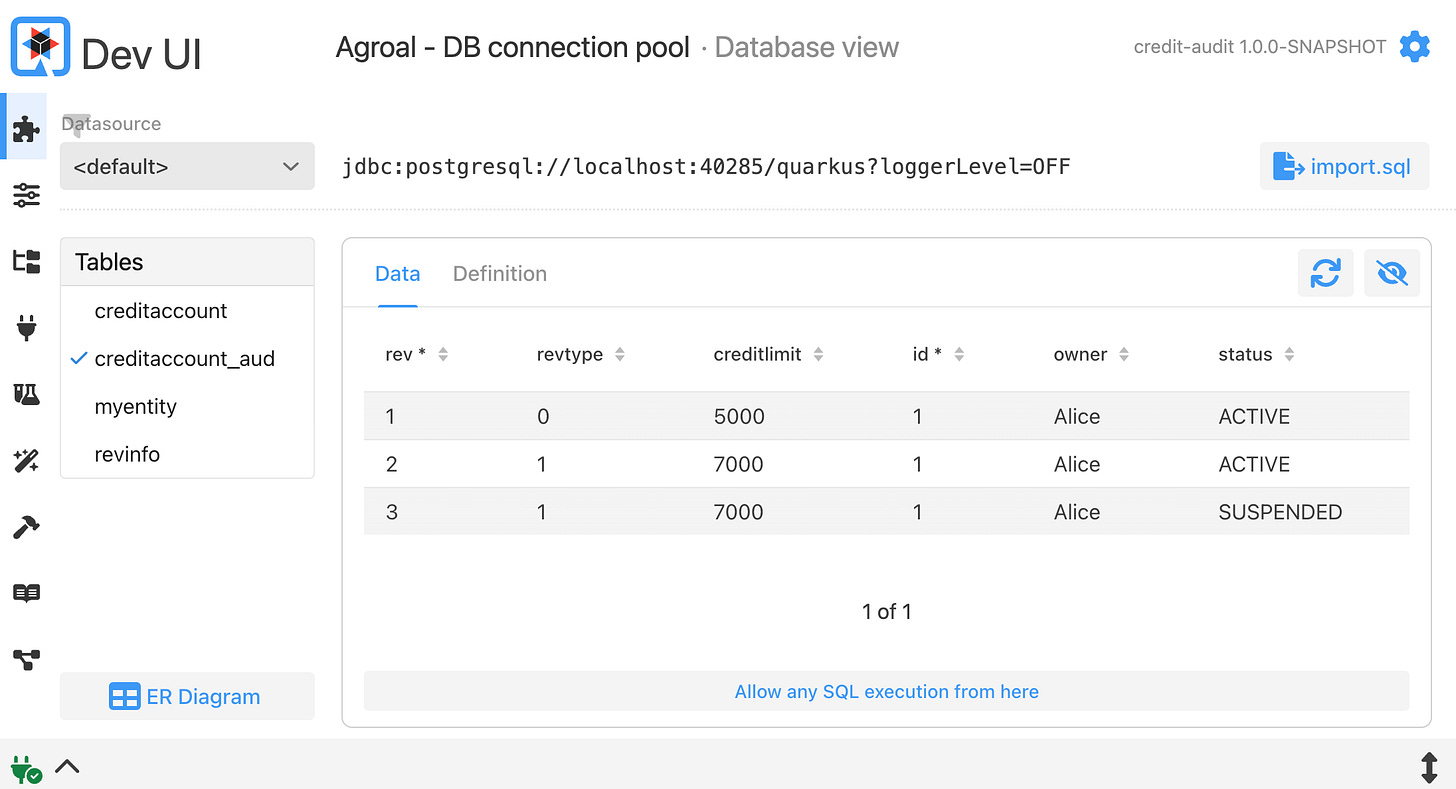

For our CreditAccount entity, Hibernate creates three tables, not one.

The first is the table you expect, usually named creditaccount. This table always represents current truth. At any moment, it contains exactly one row per account, and that row reflects the latest committed state. If a transaction rolls back, this table never sees the failed change.

The second table is the audit table, creditaccount_AUD. This table is where Envers earns its keep. Every successful transaction that modifies a @Audited entity inserts a new row into this table. Not a diff. Not a delta. A full snapshot of the entity as it existed at commit time. If the credit limit changes from 5,000 to 7,000, the audit table now contains two rows for the same entity ID, each representing a complete historical state.

The third table is the quiet but critical one: REVINFO.

What the REVINFO Table Really Represents

REVINFO is not tied to a single entity. It represents transactions.

Every time a transaction commits and at least one audited entity is modified, Envers creates a new revision entry in REVINFO. That revision is then referenced by all audit rows created in that transaction, across all audited entities.

Conceptually, a revision answers one question:

“What changed together, at the same time, in one atomic commit?”

A typical REVINFO table contains at least two columns:

A numeric revision identifier, usually called

REVA timestamp column, usually called

REVTSTMP

The revision number is monotonically increasing. It is not an entity version and it is not scoped to a table. It is global within the persistence unit. That design guarantees ordering even if timestamps collide or clocks drift.

The timestamp is captured at commit time and stored as milliseconds since epoch. It represents when the database transaction became durable, not when some application method started executing. This distinction matters when you are reconstructing incidents under load or during partial failures.

How These Tables Work Together

When you update a credit limit inside a transaction, the following happens atomically:

Hibernate updates the row in creditaccount.

Hibernate inserts a new row into creditaccount_AUD containing the full entity state.

Hibernate either creates a new row in REVINFO or reuses the current revision if multiple audited entities were changed in the same transaction.

The audit row references the revision ID from REVINFO.

If the transaction rolls back, none of these rows exist. There is no orphaned audit data, no phantom history, and no need for cleanup jobs. This is why Envers must live inside the ORM layer and not in application-level listeners or log appenders.

Why Envers Stores Snapshots, Not Diffs

At first glance, storing full snapshots looks wasteful. In practice, it is what makes audits reliable.

Diffs require interpretation. Interpretation requires context. Context disappears over time. Snapshots do not. When an auditor asks what the credit account looked like at a specific point in time, Envers can answer directly, without replaying events, without applying patches, and without relying on application logic that may no longer exist.

This design also means that schema changes are survivable. If you add a column later, older audit rows simply have it as null. You still retain historical truth instead of breaking your audit pipeline.

The Hidden Superpower of REVINFO

Because REVINFO is transaction-scoped, not entity-scoped, it becomes the anchor point for cross-entity auditing.

If a future transaction updates a CreditAccount, a CustomerProfile, and a RiskAssessment entity together, all of their audit rows will reference the same revision. That allows you to reconstruct what changed together, not just what changed individually. In real investigations, that correlation is often more valuable than the entity data itself.

This is also why exposing revision numbers and timestamps together is so important. Revision numbers give you ordering guarantees. Timestamps give you temporal context. Together, they turn raw history into something humans can reason about.

Writing Through a Transaction Boundary

Auditing is meaningless if changes leak outside transactions. We make this explicit in the service layer.

package com.mainthread.audit.service;

import com.mainthread.audit.domain.CreditAccount;

import jakarta.enterprise.context.ApplicationScoped;

import jakarta.transaction.Transactional;

@ApplicationScoped

public class CreditAccountService {

@Transactional

public CreditAccount create(String owner, long limit) {

CreditAccount account = new CreditAccount();

account.owner = owner;

account.creditLimit = limit;

account.status = CreditAccount.Status.ACTIVE;

account.persist();

return account;

}

@Transactional

public CreditAccount updateLimit(Long id, long newLimit) {

CreditAccount account = CreditAccount.findById(id);

account.creditLimit = newLimit;

return account;

}

@Transactional

public CreditAccount suspend(Long id) {

CreditAccount account = CreditAccount.findById(id);

account.status = CreditAccount.Status.SUSPENDED;

return account;

}

}Each method is a business event. Each event maps cleanly to an Envers revision. There are no hidden updates, no detached entities, and no side effects that escape the transaction.

Exposing the API Without Leaking Internals

The REST layer stays boring, which is exactly what you want.

package com.mainthread.audit.api;

import com.mainthread.audit.domain.CreditAccount;

import com.mainthread.audit.service.CreditAccountService;

import jakarta.inject.Inject;

import jakarta.ws.rs.Consumes;

import jakarta.ws.rs.POST;

import jakarta.ws.rs.PUT;

import jakarta.ws.rs.Path;

import jakarta.ws.rs.PathParam;

import jakarta.ws.rs.Produces;

@Path("/accounts")

@Consumes("application/json")

@Produces("application/json")

public class CreditAccountResource {

@Inject

CreditAccountService service;

@POST

public CreditAccount create(CreateAccountRequest request) {

return service.create(request.owner, request.limit);

}

@PUT

@Path("{id}/limit")

public CreditAccount updateLimit(@PathParam("id") Long id, UpdateLimitRequest request) {

return service.updateLimit(id, request.limit);

}

@POST

@Path("{id}/suspend")

public CreditAccount suspend(@PathParam("id") Long id) {

return service.suspend(id);

}

public static class CreateAccountRequest {

public String owner;

public long limit;

}

public static class UpdateLimitRequest {

public long limit;

}

}Nothing here knows about Envers. That separation is intentional. Auditing is a persistence concern, not an API feature.

Reading Audit History Like an Auditor Would

This is where most examples stop. We do not.

Hibernate Envers provides an AuditReader API that lets you query historical state with the same discipline you apply to live data.

package com.mainthread.audit.audit;

import java.time.Instant;

import java.util.Date;

import java.util.List;

import org.hibernate.envers.AuditReader;

import org.hibernate.envers.AuditReaderFactory;

import com.mainthread.audit.domain.CreditAccount;

import jakarta.enterprise.context.ApplicationScoped;

import jakarta.inject.Inject;

import jakarta.persistence.EntityManager;

@ApplicationScoped

public class CreditAccountAuditService {

@Inject

EntityManager em;

public List<Number> revisions(Long accountId) {

AuditReader reader = AuditReaderFactory.get(em);

return reader.getRevisions(CreditAccount.class, accountId);

}

public CreditAccount atRevision(Long accountId, Number revision) {

AuditReader reader = AuditReaderFactory.get(em);

return reader.find(CreditAccount.class, accountId, revision);

}

public AuditSnapshot snapshot(Long accountId, Number revision) {

AuditReader reader = AuditReaderFactory.get(em);

CreditAccount account = reader.find(CreditAccount.class, accountId, revision);

if (account == null) {

return null;

}

Date revisionDate = reader.getRevisionDate(revision);

return new AuditSnapshot(

account,

revision.longValue(),

revisionDate.toInstant());

}

public record AuditSnapshot(

CreditAccount account,

long revision,

Instant timestamp) {

}

}This code reads like normal JPA because it is. You can retrieve the full state of an entity as it existed at any revision. No diff parsing. No log correlation. Just data.

The Audit Resource

We expose revisions as raw identifiers because that is what Envers guarantees to be stable. Trying to invent your own semantic versioning on top of audit history usually ends in confusion. A revision is a revision. Treat it as such.

Returning a full CreditAccount snapshot instead of a diff is also deliberate. In audit conversations, diffs raise follow-up questions. Snapshots answer them. You can see the entire state as it existed, not just what changed.

Notice that this endpoint does not annotate anything with @Transactional. Audit reads do not need write transactions, and letting Quarkus manage a simple read-only EntityManager scope is sufficient and safer.

package com.mainthread.audit.api;

import java.util.List;

import com.mainthread.audit.audit.CreditAccountAuditService;

import com.mainthread.audit.audit.CreditAccountAuditService.AuditSnapshot;

import jakarta.inject.Inject;

import jakarta.ws.rs.GET;

import jakarta.ws.rs.NotFoundException;

import jakarta.ws.rs.Path;

import jakarta.ws.rs.PathParam;

import jakarta.ws.rs.Produces;

@Path("/accounts/{id}/audit")

@Produces("application/json")

public class CreditAccountAuditResource {

@Inject

CreditAccountAuditService auditService;

@GET

@Path("/revisions")

public List<Number> revisions(@PathParam("id") Long accountId) {

return auditService.revisions(accountId);

}

@GET

@Path("/revisions/{revision}")

public AuditSnapshot revision(

@PathParam("id") Long accountId,

@PathParam("revision") Long revision) {

AuditSnapshot snapshot = auditService.snapshot(accountId, revision);

if (snapshot == null) {

throw new NotFoundException(

"No revision " + revision + " for account " + accountId);

}

return snapshot;

}

}This endpoint is intentionally explicit. There is no “latest” shortcut, no pagination magic, and no attempt to abstract revision numbers away. Audit trails are not UX features. They are forensic tools.

Answering the Question That Started This

When compliance asks what happened, you can now answer precisely.

You can show the credit limit before and after each change. You can show the exact transaction boundaries. If you extend this with custom revision metadata, you can also show who triggered the change and from which subsystem.

That is not logging. That is accountability.

Production Hardening and Trade-Offs

Envers increases write amplification. Every update writes more rows. That is the price of traceability. In systems where updates are rare and consequences are high, this trade is correct. In high-frequency telemetry systems, it is not.

You should also be aware that Envers snapshots entire entities. Large aggregates grow expensive to audit. In real systems, that pressure often forces better aggregate design, which is a hidden benefit.

Security-wise, audit tables deserve stricter access control than live tables. They contain historical truth, not just operational state.

Verifying the System

Start your application in dev mode:

quarkus devCreate an account, update it twice,

curl -X POST http://localhost:8080/accounts \

-H "Content-Type: application/json" \

-d '{"owner":"Alice","limit":5000}'curl -X PUT http://localhost:8080/accounts/1/limit \

-H "Content-Type: application/json" \

-d '{"limit":7000}'curl -X POST http://localhost:8080/accounts/1/suspendthen look at the revisions:

curl http://localhost:8080/accounts/1/audit/revisionsQuerying revisions will return three distinct snapshots.

[1,2,3]Each one is defensible. Each one is immutable.

curl http://localhost:8080/accounts/1/audit/revisions/2 | jqReturns the revision itself with auditing information:

{

"account": {

"id": 1,

"owner": "Alice",

"creditLimit": 7000,

"status": "ACTIVE"

},

"revision": 2,

"timestamp": "2026-01-02T04:36:22.136Z"

}It answers what, when, and in which order, without interpretation.

Closing the Loop

We started with a system that worked but could not explain itself. We ended with one that records its own history as part of doing business.

Envers is not glamorous, but when the auditor calls back, it is the difference between guessing and knowing.